Part 1 of this article discusses the physiology and causes of dystocia in horses, as well as the equipment and drugs needed for managing dystocia and assessing, planning and diagnosing in the field. This article considers planning and communication skills, correcting dystocia and prognosis for mare and foal.

Planning and communication

Once the nature of the dystocia has been diagnosed, a concise conversation with the owners should ensue. The likely prognosis for mare, foal and subsequent fertility, as well as costs associated with assisted vaginal delivery, controlled vaginal delivery, caesarian section and fetotomy (if appropriate) should be discussed. Owners may need to be asked whether preservation of the mare's life, or delivery of a live foal is the priority. If the mare's survival is the primary consideration, it may be pertinent to ask whether that decision is caveated by sound future fertility.

This discussion can be a difficult one, but is vital in determining the next step in order to optimise the outcome. Often the decision is influenced by finances, obstetrical expertise and proximity to a specialist referral centre. Protracted manual manipulations are not recommended if future fertility is the primary concern, because of the abrasive nature of repeatedly introducing and withdrawing an arm, as well as unavoidable bacterial contamination of the uterus. Resolute decision-making is key; if initial attempts at manipulating the neonate are unsuccessful, an alternative course must be considered. If a suitable hospital is nearby, and finances permit it, prompt referral for controlled vaginal delivery or caesarian section may represent the most favourable chance of a positive outcome for mare and foal survival, as well as future fertility.

Unfortunately, fetotomy is frequently a decision of last resort; by which time referral has been declined, significant vaginal and cervical trauma has been sustained, and the mare may even have been anaesthetised in the field for a controlled vaginal delivery. If the foetus is found to be dead at the start, one or two appropriately-placed fetotomy cuts can permit prompt delivery, while inflicting minimal soft-tissue trauma to the mare. The specific fetotomy techniques recommended for each diagnosis are beyond the scope of this article, but can be found in the literature (Frazer, 2011b; Frazer, 2007).

Basic principles for correcting dystocia

Long extremities, space limitations and intense abdominal straining makes manipulation of the equine foetus more complicated than in other species. Uterine rupture is a risk factor with foetal repulsion. Therefore, tocolytics and copious warm, volume-expanding lubricant are recommended, to induce some degree of myometrial relaxation, as well as increasing available space for manipulations. Evidence of haemorrhage may be suggestive of uterine laceration, which should be ruled out via abdominocentesis before obstetrical lubricant is infused into the uterus. Iatrogenic uterine tears are more commonly found in the uterine body, while tears located at the gravid horn tip are more likely caused by foetal hindlimb thrusts (Frazer, 2011a).

Traction applied to limbs during assisted vaginal delivery are simply to provide assistance. Traction by hand or with ropes may suffice, though often chains with handles are used for their superior grip. Chains should be placed above the fetlock to grip the distal third metacarpal/tarsal bone (MCIII/MTIII), with the eye of the chain located dorsally. Some authors recommend applying a second half-hitch below the fetlock, around the proximal phalanx, to reduce the risk of crush fracture (Frazer, 2011a). Torque should accompany maternal expulsive efforts and would be intermittently applied – which is vital to allow for complete cervical and vaginal dilation. No more than two or three individuals should be asked to assist and mechanical calving aids should never be used. Injudicious, excessive force risks trauma to the mare's reproductive tract or severe foetal injury, such as rib fracture, diaphragmatic hernia or bladder rupture (Jean et al, 1999; Frazer, 2007).

Ropes applied to the head should be used to direct the head into the pelvic canal only, with traction kept to a minimum. If a rope snare cannot be placed behind the ears and into the mouth of the foetus, a small mandibular snare may suffice in gently guiding the head. However, the delicate mandible can easily fracture if excessive traction is applied (Frazer, 2007). Meanwhile, blunt eye hooks can be very useful in guiding the head in cases where the foetus has been found to be dead.

It is important to emphasise that a normal-sized equine foetus approaching the pelvic canal of a normal mare in a normal presentation, position and posture should be delivered easily, and only a minimal amount of traction should be necessary. If progress is not being made, traction should promptly cease and the situation be thoroughly reassessed. Before traction is applied to any apparently normally disposed foetus, the author recommends that the ventral pelvic brim is quickly assessed using a gloved, lubricated arm to rule out the presence of one or more hindlimbs (Tables 1–4, Figures 1-9).

Table 1. Dystocia involving cranial longitudinal presentation

| Normal presentation with abnormal position and/or posture. Incomplete rotation of foetus into dorsosacral position and/or incomplete extension of forelimbs and head to engage pelvic canal. | |

Causes:

|

|

| Diagnosis | Recommended approach |

|---|---|

| Feto-pelvic disproportion: absolute – foetus too large to transit maternal pelvic canal, or more commonly, relative – maternal pelvic canal or caudal reproductive tract too narrow (incomplete cervical relaxation in primiparous mare or old pelvic injury) to allow transit of normal-sized foetus.Suspect if foetal maldisposition, congenital abnormality and uterine inertia have been ruled out; palpable pelvic or vaginal narrowing or abnormality; primiparous mare. |

|

| Dorsopubic/dorsoilial position: incomplete rotation of the cranial foetus from dorsopubic to dorsosacral.Suspect if soles of foetal forefeet are not orientated ventrally. |

|

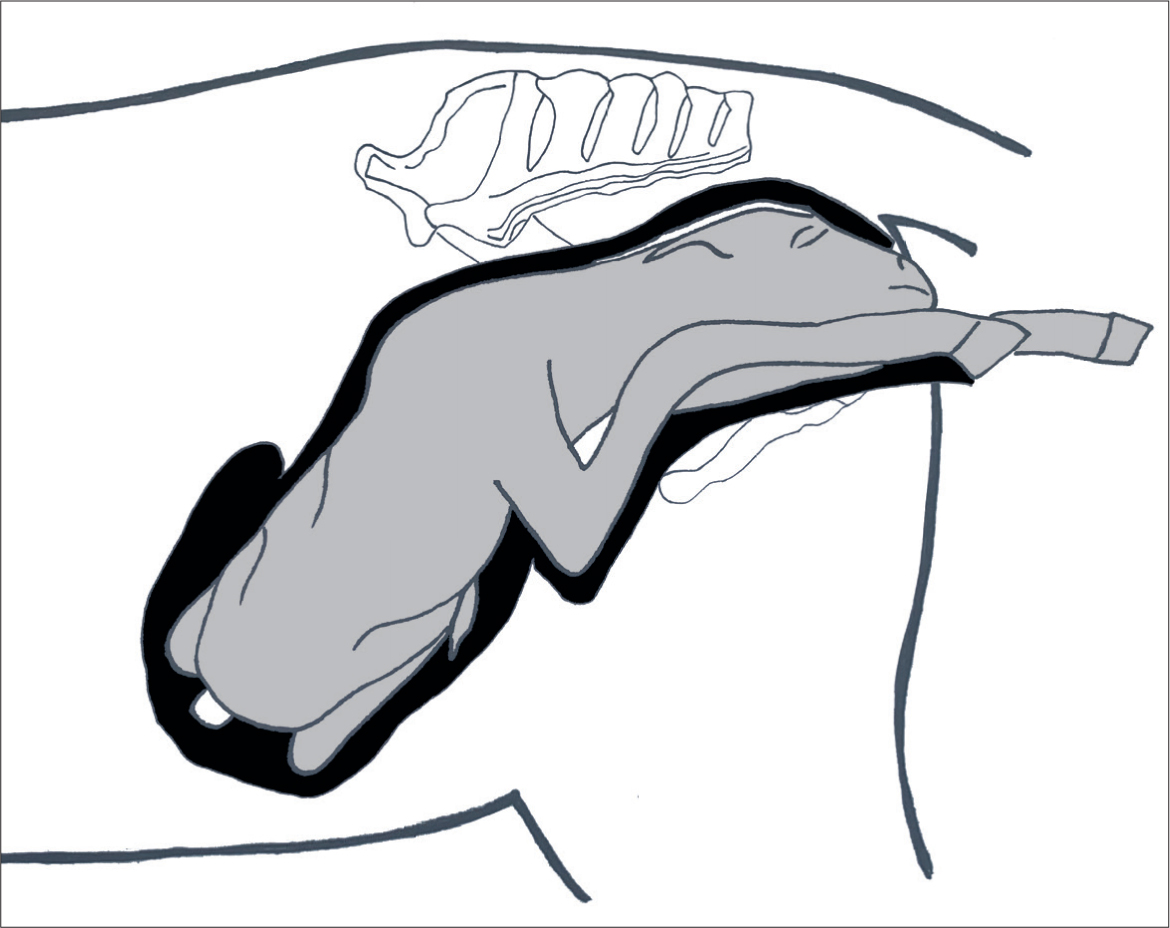

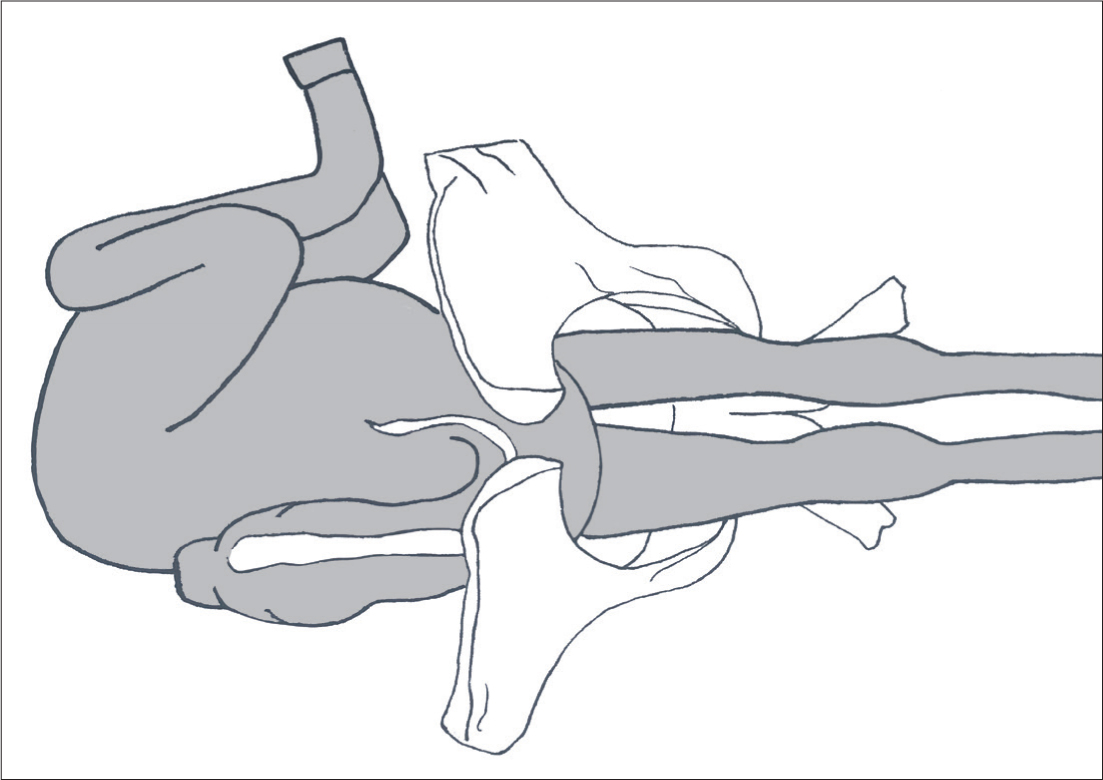

| ‘Elbow-lock’ posture - incomplete extension of one or both elbow joints (Figure 6).Suspect if nose of foetus overlies fetlock as opposed to proximal MCIII. Foetal olecranon palpable at pelvic brim. |

|

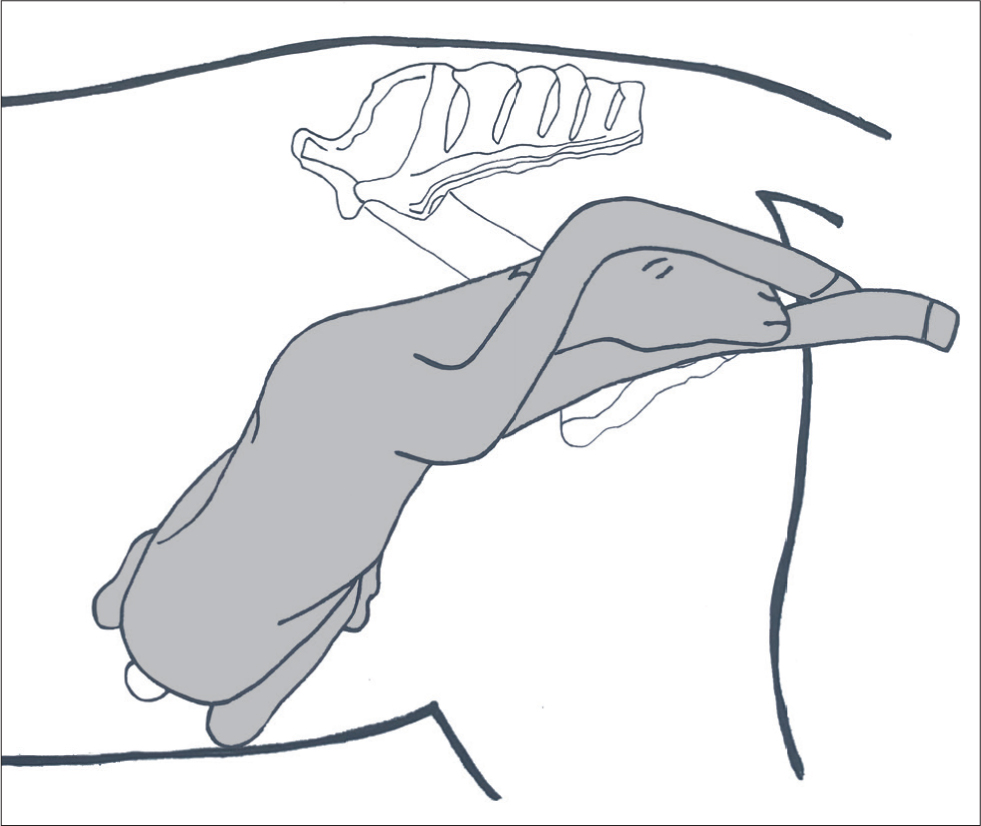

| Foot-nape' posture: displacement of forelimb(s) over foetal head and impingement against dorsal vagina Figure 7).Suspect if one or both feet located dorsally to foetal crown; palpable lacerations in dorsal vaginal wall; or if foot seen protruding through mare's anus. |

|

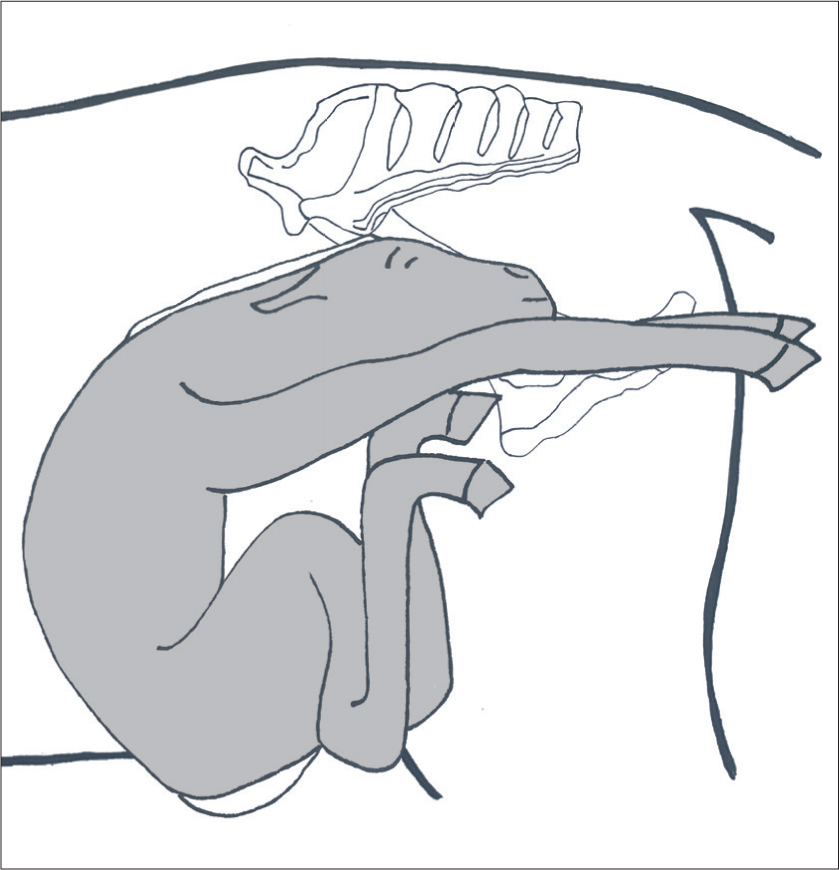

| Carpal flexion posture: failure of one or both carpi to extend fully.Suspect if one or both forelimbs fail to appear through the vulvae. |

|

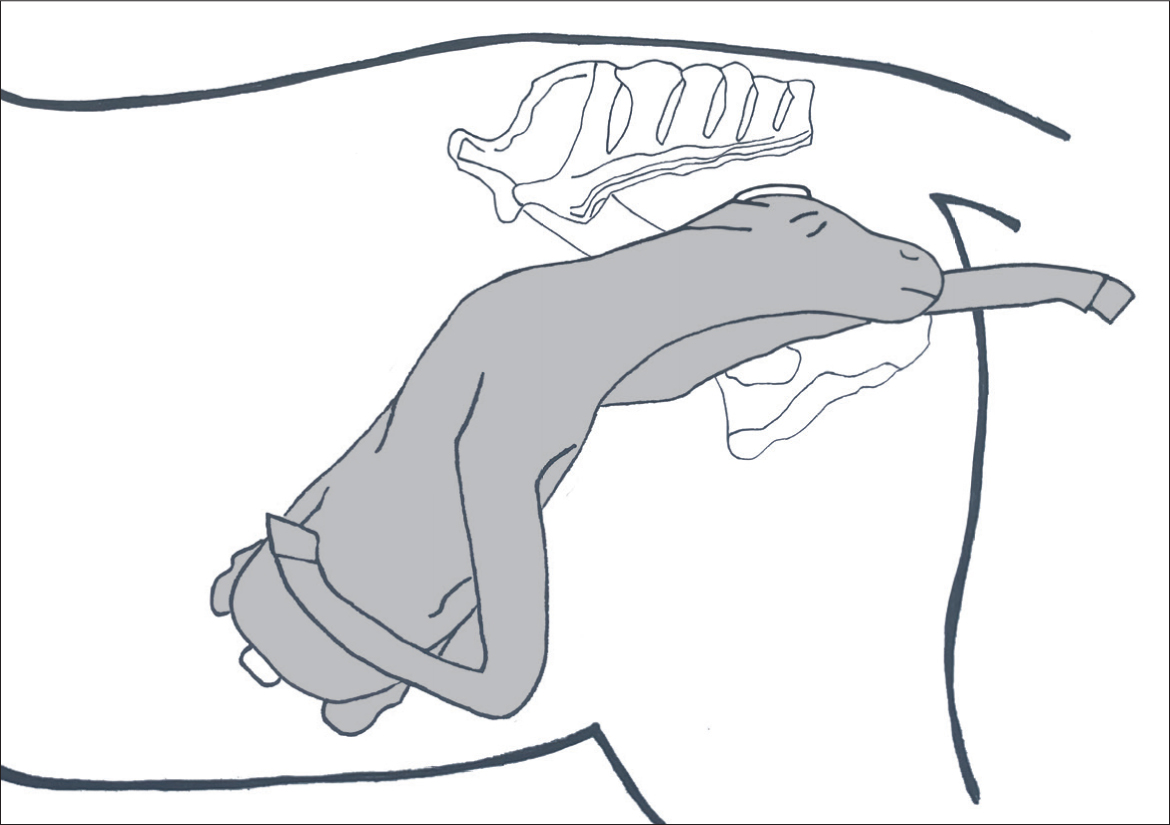

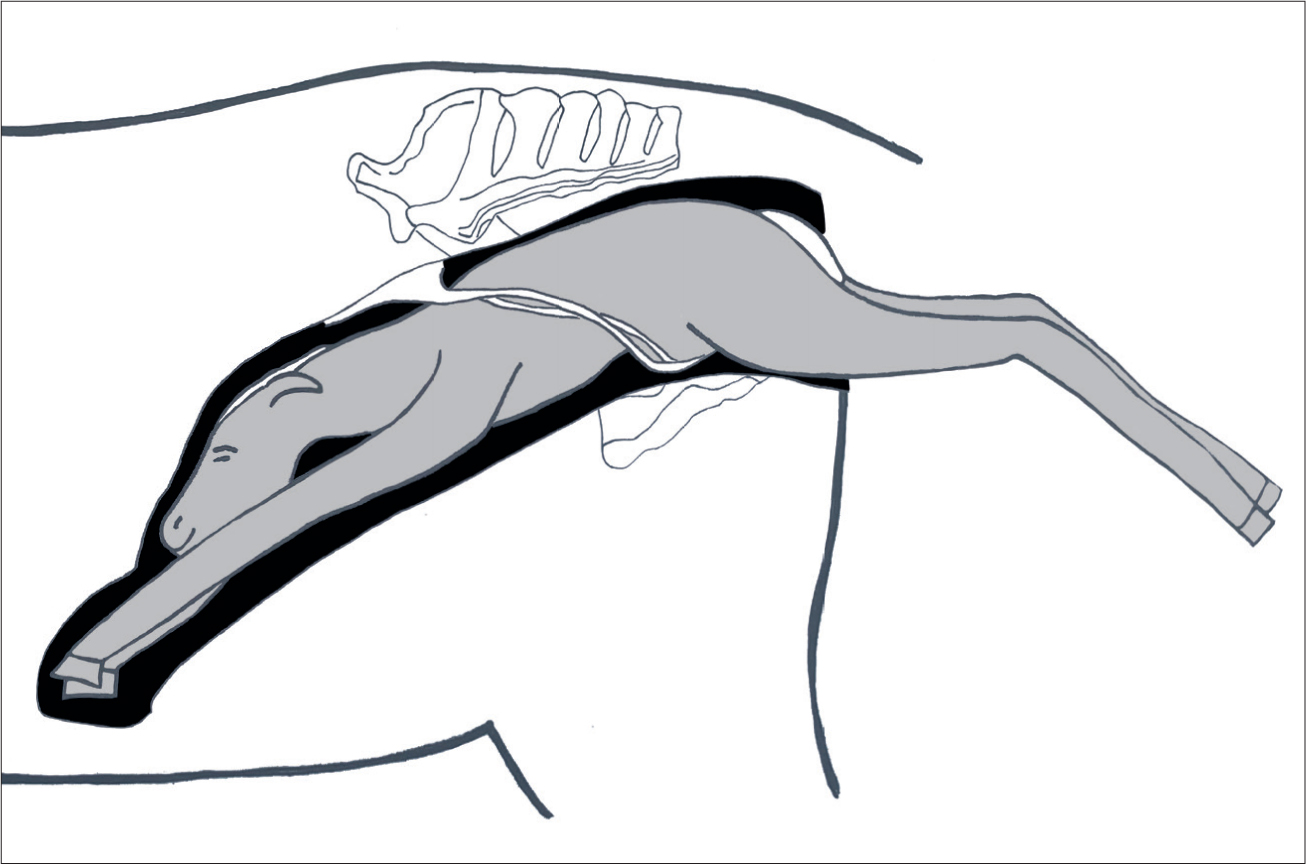

| Shoulder flexion posture - failure of one or both shoulders to extend fully (Figure 8).Suspect if one or both forelimbs fail to appear through the vulvae. |

|

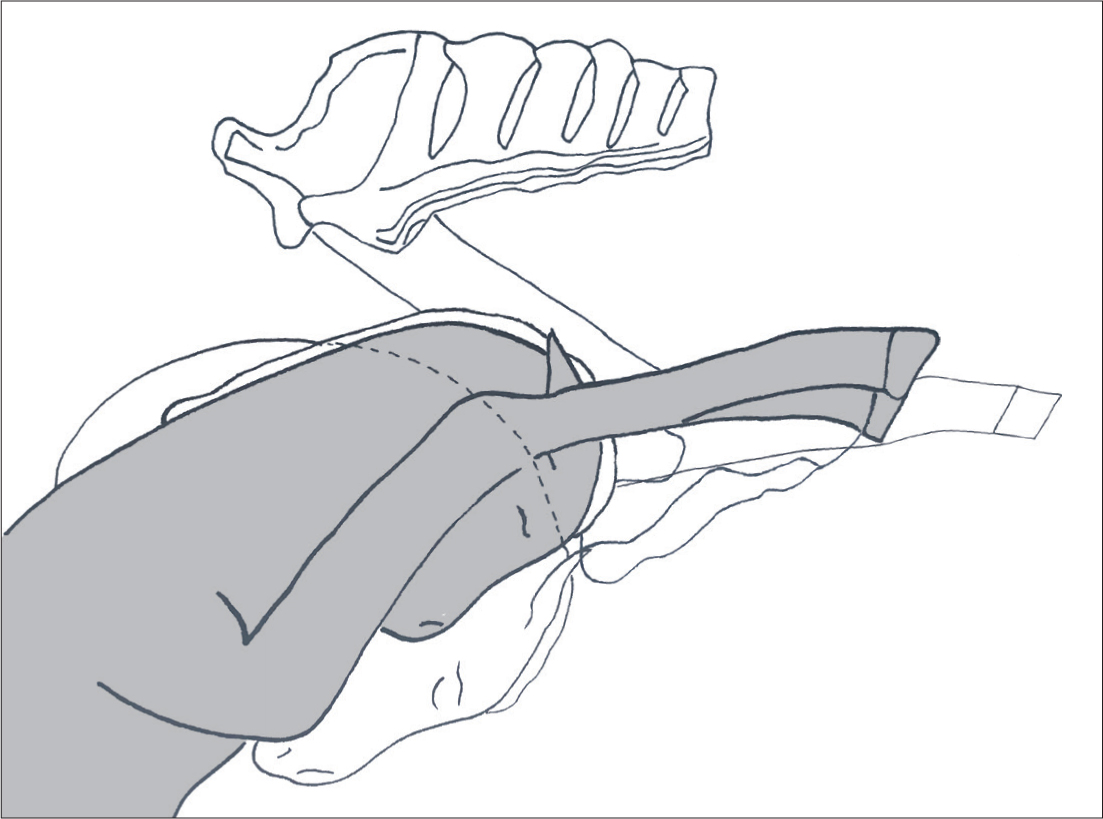

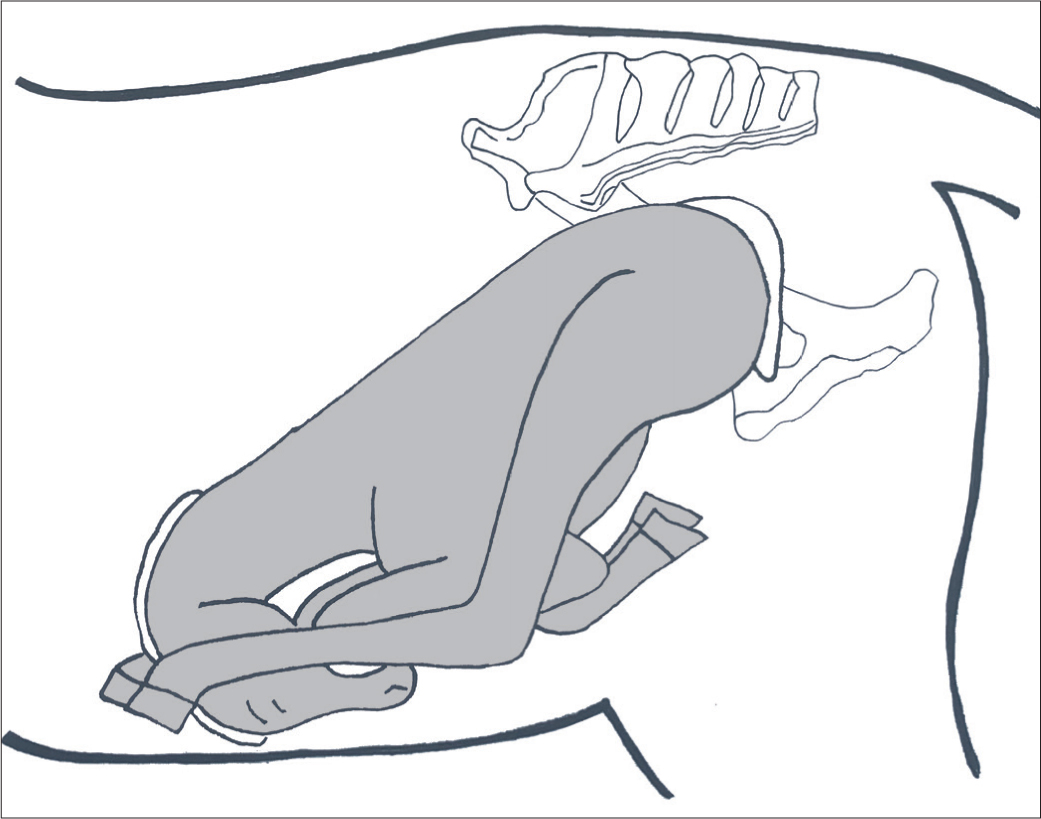

| Ventrally deviated head and neck posture - ventral flexion of the cervical spine, often accompanied by normal extension of the forelimbs (Figure 9).Suspect if foetal muzzle fails to appear through the vulvae with the fore feet. |

|

| Laterally deviated head and neck posture - lateral flexion of the cervical spine, often caused by torticollis (Figure 10).Suspect if foetal muzzle fails to appear through the vulvae with the fore feet. |

|

Table 2. Dystocia involving caudal longitudinal presentation

| Caudal longitudinal presentation is seen in 1% of foalings. It follows failure of the sequence of mid-gestational events that usually result in entrap-ment of the foetal hindlimbs in a single gravid horn, which, in normal circumstances, helps to ensure cranial longitudinal presentation in 98.9% of foalings. Mares that deliver foals in caudal presentation may be more likely to do so again so should be considered high risk with subsequent foalings (Newcombe and Kelly, 2018). | |

| The active foetal responses eliciting foetal rotation and forelimb and neck extension seen in normal circumstances often fails to occur in caudally presented foetuses, and therefore the hind joints often remain flexed, leading to dystocia. | |

| There is an elevated risk of umbilical cord compression by the foetal thorax, or umbilical rupture, in caudally-presented foetuses, and subsequent hypoxia; which intensifies the necessity for swift intervention and prompt decision-making. | |

| Diagnosis | Recommended approach |

|---|---|

| Uncomplicated caudal longitudinal presentation Suspect if feet appear with soles orientated dorsally. Foetal hocks palpable in birth canal (Figure 11). |

|

| Hock flexion posture - foetal hips ex-tended but hocks tightly flexed. Calcaneal protuberances palpable in birth canal. |

|

| Bilateral hip flexion (breech) posture - foetal hips flexed and hocks fully extended alongside foetal trunk (Figure 12).Suspect if no foetal extremities appear. Foetal rump and tail palpable at pelvic inlet. |

|

Table 3. Dystocia involving transverse presentation

| Transverse presentations are seen in 0.1% of foalings so are less common than caudal longitudinal presentations though are also due to failure of the foetal hindlimbs to become trapped in the gravid uterine horn. Therefore, the entire foetus occupies the uterine body and the placenta extends into variable portions of each horn. | |

| During parturition, either all four limbs, or the foetal dorsum approach the pelvic inlet. Often, mares fail to proceed beyond stage 1, chorioallantoic rupture may fail to occur, and abdominal straining may not be seen as the Ferguson reflex is not stimulated. | |

| Diagnosis | Recommended approach |

|---|---|

| Dorso-transverse presentation Foetal spine presents at the pelvic inlet with no limbs palpable. |

|

| Ventro-transverse presentation All four foetal limbs and head palpable at the pelvic inlet (Figure 13). Note: Twinning must be ruled out as a differential. |

|

| Hip flexion with impaction of one (hurdling posture) or both (dog-sitting posture) hindlimbs Foetus initially appears to present in cranial longitudinal orientation before progress ceases following partial delivery of the cranial portion of the foetus, due to the presence of one or both feet of the flexed hindlimbs obstructing the pelvic inlet. Therefore, considered a variant of ventro-transverse presentation (Figure 14). |

|

Table 4. Dystocia involving foetal developmental abnormalities

| Diagnosis | Recommended approach |

|---|---|

| Contracted foal syndrome – any combination of flexural deformities involving one or multiple limbs, and/or vertebral deformity such as scoliosis or torticollis preventing normal extension of extremities towards pelvic inlet. |

|

| Hydrocephalus – delivery impeded by markedly enlarged skull. |

|

Postpartum management

The foal

If a live foal is delivered vaginally, the obstetrician's initial focus should be on its viability. Prolonged parturition, premature placental separation and umbilical compression, or early rupture all increase the risk of foetal asphyxia and subsequent respiratory arrest, which is almost always primary in the equine neonate. Therefore, cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation is more likely to be necessary following dystocia.

Normal foals should start breathing regularly within 30 seconds postpartum, while the heart rate should be around 70 beats per minute (bpm), and have a regular rhythm. Resuscitation is required if a heart beat or respiratory efforts are absent; if the heart rate is less than 50 bpm; or if irregular gasping continues for longer than 30 seconds (Corley and Axon, 2005). A review of the approach to foal resuscitation is beyond the scope of this article. As well as assessing the foal's clinical vital signs, a thorough examination of the neonatal foal should be performed to check for rib fracture and obvious congenital abnormalities. Within 5 minutes, a normal foal should raise its head and neck, and assume a sternal position. Typically a foal stands within 1 hour. Evidence of cerebro-cortical disease such as prolonged lateral recumbency, uncoordination, wandering and impaired teat seeking is seen with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (neonatal maladjustment syndrome). Intermittent seizures are seen in some neonates (McSloy, 2008). Treating severely compromised newborn foals can be extremely labour intensive, therefore referral to a neonatal intensive care unit is strongly recommended.

The mare

The obstetrician should also perform a thorough examination of the mare, including an internal manual examination per vaginum to rule out the presence of twins and to assess for evidence of uterine lacerations, or significant uterine or vaginal haemorrhage. The broad ligament can be evaluated for evidence of haematoma via transrectal palpation. A cursory assessment of the mare's vital signs should be made, primarily for any indication of internal haemorrhage (elevated heart and/or respiratory rate, mucous membrane pallor and increased capillary refill time). The mare may remain in lateral recumbency for several minutes before rising. A mild-to-moderate degree of abdominal discomfort may be considered normal, especially during stage 3 parturition. However, if signs of colic are severe, further investigations may be necessary.

Abdominocentesis can be highly useful in ruling out internal haemorrhage, peritonitis or rupture of a gastrointestinal viscus. Retention of the foetal membranes is more likely following dystocia (Vandeplassche et al, 1971). Owners should be advised to administer low-dose oxytocin intramuscularly (10 iu, hourly) to encourage placental expulsion. If the placenta is not passed within 3–6 hours postpartum, intervention is recommended via a variety of approaches (Gormley, 2019; Threlfell, 2011). A moderate degree of perineal oedema and minor mucosal trauma are common following dystocia. Analgesia should be provided using NSAIDs, for example flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg intravenously twice daily), and mineral oil administration via nasogastric intubation is recommended by some authors to lubricate faecal passage. Oral fluid consumption should be monitored closely and supplemented via a nasogastric tube, if necessary, to reduce the risk of faecal impaction. Septic metritis is a potential risk factor following bacterial colonisation of retained foetal membranes or devitalised necrotic uterine tissue; which can quickly lead to life-threatening endotoxaemia and acute laminitis. Therefore, prophylactic broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy is recommended in some cases, and these can be provided orally or parenterally.

Prognosis

The prospects for mare and foal survival, and future fertility following dystocia, vary widely based on the specific cause of dystocia, management approach, time to resolution and quality of aftercare. Morley and Townsend (1997) reported a 33% risk of foetal or neonatal death in cases of dystocia that required veterinary intervention. In an online communication, Rossdales Equine Hospital reported a mare survival rate of over 80% following general anaesthesia for controlled vaginal delivery or caesarian section, while foal survival was 41% after controlled vaginal delivery and just 19% after caesarian section. McCue and Ferris (2012) found a delay of more than 40 minutes following the onset of stage 2 was associated with a significant rise in foal mortality, while Norton et al (2007) reported a 10% increase in foal mortality for every 10-minute delay in delivery beyond 30 minutes. Rás et al (2014) reported a mare survival rate of 84% following fetotomy, a 31% pregnancy rate among mares bred in the same season and 44% for those bred the following season.

Conclusion

Although most foalings proceed uneventfully, dystocia is a genuine risk with any parturition. A rapid and explosive stage 2, coupled with long foetal extremities and distinct limitations on intrapartum placental function, all elevate the urgency associated with equine dystocia when compared with other species. The prognosis for mare and foal is linked to the timeliness with which intervention is provided and this is, in turn, depends on the monitoring system in place and the ability to detect deviations from the norm as soon after the onset of stage 2 as possible. In many cases, the outcome is inextricably linked to the ability of the obstetrician to act in a calm and logical fashion in response to the clinical needs and priorities of mare/foal and owner, respectively. Composed decision-making in what is a highly adrenalised and stressful situation is key. Regular critical assessment of actual progress achieved over time elapsed and a willingness to change tack is essential. If a suitable specialist facility is located nearby, the first question any clinician should ask themselves, regardless of obstetrical experience, is whether the case should be immediately referred. Finally, if the foetus is found to be dead, the obstetrician should consider whether fetotomy is a logical early approach to resolving the dystocia, as opposed to an option of last resort.

KEY POINTS

- A logical, pragmatic approach must be adopted in all cases of dystocia

- Communication with connections is essential in order to allow the approach to be tailored towards prioritising the outcome for foal, mare and/or future fertility.

- If initial attempts at resolution fail to result in perceivable progress, an alternative strategy should be attempted.

- Referral for caesarian section should be considered at the outset.

- Fetotomy should not be regarded as an option of last resort.

- A head snare should be applied before mutation is attempted.

- Traction applied should assist mare's intermittent expulsive efforts only and should not exceed that provided by two to three individuals.